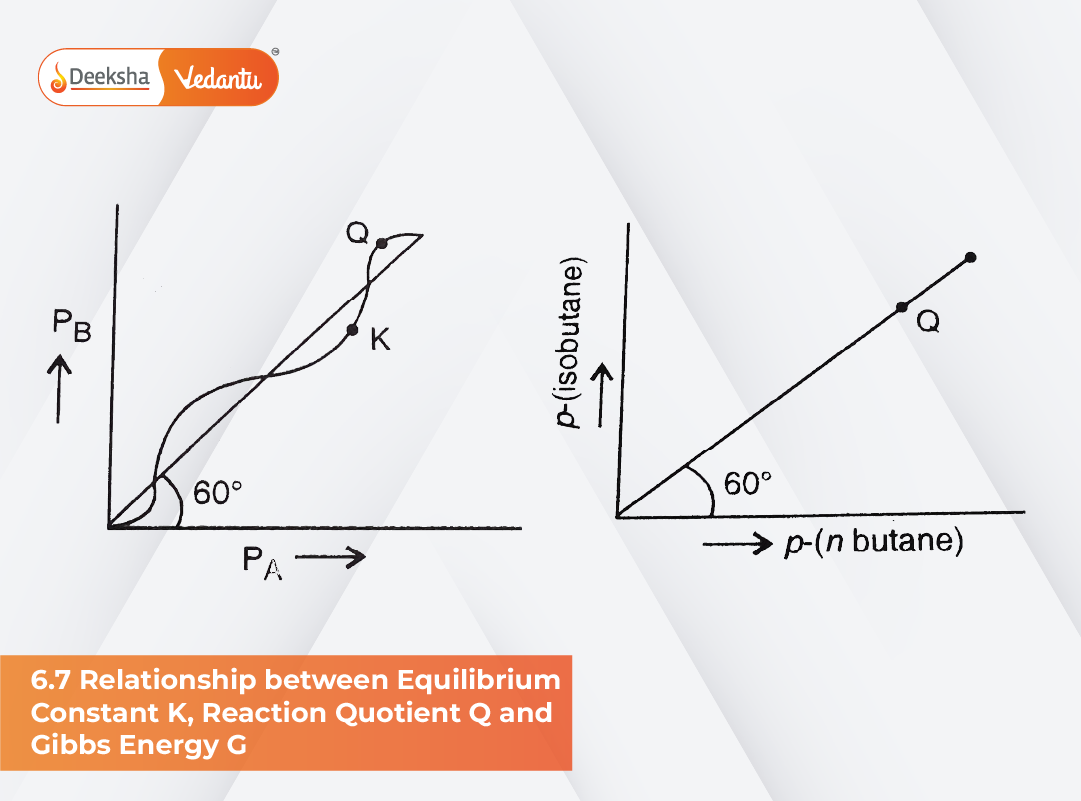

The equilibrium constant (K) is a fundamental quantity in thermodynamics that defines the ratio of products to reactants at equilibrium. While K does not depend on the rate of reaction, it is deeply connected to the energy changes occurring during a chemical transformation. This link is governed by the concept of Gibbs free energy (ΔG), which determines whether a reaction is spontaneous, non-spontaneous, or in equilibrium.

Understanding the interplay between K, Q, and ΔG allows chemists to predict both the direction and extent of reactions, and it serves as a cornerstone concept in physical chemistry and chemical equilibrium.

Understanding Gibbs Free Energy and Reaction Spontaneity

The Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) indicates the maximum amount of useful work obtainable from a chemical reaction at constant temperature and pressure. It helps determine whether a reaction proceeds on its own or requires energy input.

- When ΔG < 0, the reaction is spontaneous and naturally proceeds in the forward direction, forming more products.

- When ΔG > 0, the reaction is non-spontaneous, meaning it will not occur without external energy; however, its reverse reaction will be spontaneous.

- When ΔG = 0, the reaction is in dynamic equilibrium, and no net change in the concentrations of reactants and products occurs.

This thermodynamic understanding bridges chemical equilibrium with energy concepts. A reaction may be fast or slow depending on kinetics, but its position of equilibrium is always determined by Gibbs free energy.

Mathematical Relationship Between ΔG and Q

The quantitative relationship between Gibbs energy and the reaction quotient (Q) is expressed as:

ΔG = ΔG° + RT lnQ

where:

- ΔG° = Standard Gibbs free energy change (under standard conditions: 1 bar pressure, 298 K temperature, and 1 M concentration)

- R = Universal gas constant (8.314 J mol⁻¹ K⁻¹)

- T = Absolute temperature in Kelvin

- Q = Reaction quotient, representing the ratio of product and reactant concentrations at any stage of the reaction

At equilibrium, the reaction quotient becomes equal to the equilibrium constant (Q = K) and ΔG = 0, giving:

0 = ΔG° + RT lnK

ΔG° = -RT lnK

This key relationship forms the foundation of thermodynamics in equilibrium. It reveals that equilibrium is reached when the system’s Gibbs energy is minimized.

Antilog and Exponential Relationship

By taking the antilogarithm of both sides, we obtain an exponential relationship:

K = e⁻(ΔG°/RT)

This equation is extremely useful for calculating K from known ΔG° values or vice versa. The exponential nature also shows how even small changes in ΔG° can cause large variations in K, emphasizing the sensitivity of equilibrium to thermodynamic parameters.

Thermodynamic Interpretation of ΔG° and K

- When ΔG° < 0, then –ΔG°/RT is positive and e⁻(ΔG°/RT) > 1, making K > 1. This implies a spontaneous reaction that strongly favors product formation.

- When ΔG° > 0, then –ΔG°/RT is negative and e⁻(ΔG°/RT) < 1, making K < 1. The reaction is non-spontaneous, and reactants are favored.

- When ΔG° = 0, K = 1, indicating that both reactants and products exist in equal proportions at equilibrium.

This relationship bridges thermodynamics and equilibrium constants, allowing a deep understanding of reaction feasibility and equilibrium position.

Example 1: Phosphorylation of Glucose

In glycolysis, glucose is phosphorylated to glucose-6-phosphate. The process has a positive ΔG°, showing it is not spontaneous without coupling to ATP hydrolysis.

Given:

ΔG° = 13.8 kJ/mol = 13.8 × 10³ J/mol

R = 8.314 J mol⁻¹ K⁻¹

T = 298 K

Formula:

ΔG° = -RT lnK

Calculation:

lnK = -ΔG° / RT

= -(13.8 × 10³) / (8.314 × 298)

= -5.569

K = e⁻⁵·⁵⁶⁹ = 3.81 × 10⁻³

The small value of K indicates that under standard conditions, the reaction barely proceeds toward product formation. In biological systems, this reaction becomes spontaneous when coupled with ATP hydrolysis, demonstrating the importance of energy coupling in metabolism.

Example 2: Hydrolysis of Sucrose

Reaction:

Sucrose + H₂O ⇌ Glucose + Fructose

Given: K = 2 × 10¹³ at 300 K

Using ΔG° = -RT lnK:

ΔG° = -8.314 × 300 × ln(2 × 10¹³)

= -8.314 × 300 × 30.63

= -7.64 × 10⁴ J mol⁻¹

Therefore, ΔG° = -76.4 kJ mol⁻¹, indicating a highly spontaneous reaction. This explains why sucrose hydrolysis occurs readily with enzymes like invertase.

Derivation of the Relationship Between ΔG, Q, and K

Let a general chemical reaction be:

aA + bB ⇌ cC + dD

At any moment, the Gibbs free energy change is given by:

ΔG = ΔG° + RT ln([C]ᶜ[D]ᵈ / [A]ᵃ[B]ᵇ)

At equilibrium: ΔG = 0 and Q = K, leading to ΔG° = -RT lnK.

This equation shows that Gibbs free energy determines how far a system is from equilibrium. When Q < K, the forward reaction is favored (ΔG < 0). When Q > K, the reverse reaction occurs (ΔG > 0).

Key Observations for NEET & JEE Aspirants

- The sign of ΔG° directly determines the spontaneity of a reaction.

- A large K value implies product dominance, while a small K value indicates reactant dominance.

- The ΔG° = -RT lnK relationship is among the most fundamental equations in physical chemistry.

- Reactions in biological systems often have positive ΔG°, but are driven forward by coupled reactions (like ATP hydrolysis).

- Temperature changes affect equilibrium constants due to their impact on Gibbs energy.

Advanced Insight: Temperature Dependence

From the equation ΔG° = ΔH° – TΔS°, we can express equilibrium dependence as:

lnK = (-ΔH° / RT) + (ΔS° / R)

This relation shows that:

- For exothermic reactions (ΔH° < 0), increasing temperature decreases K.

- For endothermic reactions (ΔH° > 0), increasing temperature increases K.

Thus, both enthalpy and entropy contribute to the position of equilibrium, providing a deeper thermodynamic understanding.

FAQs

Q1. What is the relationship between ΔG° and K?

The equation ΔG° = -RT lnK connects thermodynamic energy with equilibrium constants. Negative ΔG° means a reaction proceeds spontaneously.

Q2. What happens to ΔG at equilibrium?

At equilibrium, ΔG = 0, and the reaction quotient Q equals the equilibrium constant K.

Q3. What does a large K indicate about the reaction?

A high K value (>1) shows that the reaction strongly favors product formation.

Q4. How can spontaneity be determined using Gibbs energy?

If ΔG° < 0, the reaction is spontaneous; if ΔG° > 0, it is non-spontaneous.

Q5. What does the equation ΔG° = -RT lnK help calculate?

It allows conversion between energy data and equilibrium constants, crucial for predicting reaction direction and feasibility.

Q6. Why do biological reactions with positive ΔG° still occur?

They are coupled with highly exergonic reactions (like ATP hydrolysis) that drive them forward.

Conclusion

The interrelationship between equilibrium constant (K), reaction quotient (Q), and Gibbs free energy (ΔG) reveals how energy governs the position of equilibrium and reaction spontaneity. Understanding this concept equips students to predict whether a reaction will occur and to calculate its equilibrium constant under given conditions. For NEET and JEE aspirants, mastering this topic builds a strong foundation in physical chemistry, bridging thermodynamics and chemical equilibrium effectively.

Get Social