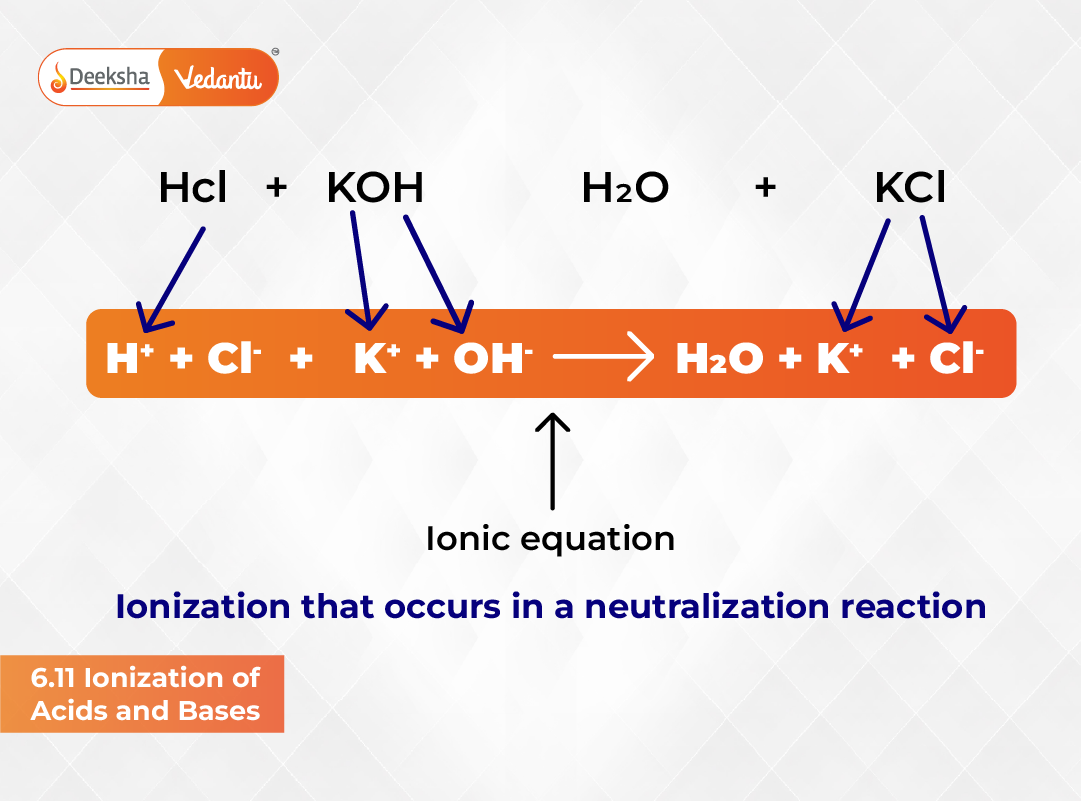

Understanding ionization is crucial for mastering acid-base chemistry. Ionization explains how acids and bases behave in aqueous solutions by describing the formation of ions. According to the Arrhenius concept, acids produce hydrogen ions (H⁺) in water, while bases yield hydroxide ions (OH⁻). Since most chemical and biological ionizations occur in aqueous media, this concept serves as a foundation for studying equilibrium in ionic systems.

Strong acids, such as perchloric acid (HClO₄), hydrochloric acid (HCl), hydrobromic acid (HBr), hydroiodic acid (HI), nitric acid (HNO₃), and sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄), ionize almost completely in water. These acids produce a large number of hydrogen ions, making them excellent proton donors. On the other hand, strong bases like sodium hydroxide (NaOH), potassium hydroxide (KOH), calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂), and barium hydroxide (Ba(OH)₂) dissociate nearly completely into hydroxide ions (OH⁻), making them efficient proton acceptors. Because these substances ionize fully, their aqueous solutions exhibit high electrical conductivity and well-defined pH values.

In contrast, weak acids such as acetic acid (CH₃COOH) and weak bases like ammonium hydroxide (NH₄OH) ionize only partially. This partial dissociation establishes an equilibrium between the ionized and non-ionized molecules, a concept central to the Brønsted-Lowry theory. Under this model, an acid acts as a proton donor while a base serves as a proton acceptor, leading to the formation of conjugate acid-base pairs.

Acid-Base Dissociation Equilibrium

Let us examine the dissociation of a weak acid:

HA(aq) + H₂O(l) ⇌ H₃O⁺(aq) + A⁻(aq)

In this reaction:

- HA is the acid (proton donor),

- H₂O is the base (proton acceptor),

- H₃O⁺ represents the conjugate acid, and

- A⁻ denotes the conjugate base.

The relative strength of acids and bases depends on their ability to donate or accept protons. Strong acids ionize almost completely, while weak acids establish a reversible equilibrium. The equilibrium always favors the formation of the weaker acid and weaker base, meaning a stronger acid donates a proton to a stronger base, establishing balance in the system.

The Ionization Constant of Acids

For a weak acid, the equilibrium can be expressed as:

HA ⇌ H⁺ + A⁻

The equilibrium constant for this dissociation, called the acid dissociation constant (Kₐ), is given by:

Kₐ = [H₃O⁺][A⁻] / [HA]

The value of Kₐ quantifies acid strength. A higher Kₐ means stronger ionization and a stronger acid, while a lower Kₐ implies a weaker acid. The logarithmic measure of Kₐ, called pKₐ, is expressed as:

pKₐ = -log Kₐ

Smaller pKₐ values correspond to stronger acids since they dissociate more easily. This relationship is central to comparing acid strengths across chemical systems.

The Ionization Constant of Water and Its Ionic Product

Water undergoes auto-ionization, even though it is a weak electrolyte:

2H₂O(l) ⇌ H₃O⁺(aq) + OH⁻(aq)

The equilibrium constant for this reaction is:

Kₚ = [H₃O⁺][OH⁻] / [H₂O]²

Since the concentration of water remains nearly constant, this term is combined into a new constant:

K𝑤 = [H₃O⁺][OH⁻]

This constant is known as the ionic product of water. At 25°C:

[H₃O⁺] = [OH⁻] = 1 × 10⁻⁷ M, therefore K𝑤 = 1 × 10⁻¹⁴.

An increase in H₃O⁺ concentration decreases OH⁻ concentration proportionally and vice versa, maintaining K𝑤 constant. This self-regulating property is key to understanding pH balance in aqueous systems.

The pH Scale

Introduced by Sørensen, the pH scale provides a logarithmic measure of hydrogen ion concentration:

pH = -log [H⁺]

At 25°C:

- Neutral solutions: [H⁺] = 1 × 10⁻⁷ → pH = 7

- Acidic solutions: [H⁺] > 1 × 10⁻⁷ → pH < 7

- Basic solutions: [H⁺] < 1 × 10⁻⁷ → pH > 7

A one-unit change in pH corresponds to a tenfold change in [H⁺]. This logarithmic relationship simplifies comparisons between strongly acidic and basic solutions. pH measurement is vital in biochemistry, medicine, agriculture, and industrial chemistry. While pH paper provides a quick visual estimate, pH meters give accurate digital readings.

Ionization Constants of Weak Acids

For a weak acid:

HA ⇌ H⁺ + A⁻

The equilibrium expression becomes:

Kₐ = [H⁺][A⁻] / [HA]

If the initial acid concentration is ‘c’ and the degree of ionization is ‘α’, then:

Kₐ = cα² / (1 – α)

Since α is very small, (1 – α) ≈ 1, giving:

Kₐ ≈ cα² → α = √(Kₐ / c)

Hence, the ionization of a weak acid decreases with increasing concentration-a fundamental principle in chemical equilibrium analysis.

Ionization of Weak Bases

For a weak base (MOH):

MOH ⇌ M⁺ + OH⁻

The base dissociation constant (Kᵦ) is expressed as:

Kᵦ = [M⁺][OH⁻] / [MOH]

With an initial concentration ‘c’ and ionization degree ‘α’:

Kᵦ = cα² / (1 – α) ≈ cα²

Lower pKᵦ values indicate stronger bases because they ionize more completely in water. The relationship between Kᵦ and pKᵦ helps compare base strengths under similar conditions.

Relation Between Kₐ and Kᵦ

For any conjugate acid-base pair:

Kₐ × Kᵦ = K𝑤

Or equivalently:

pKₐ + pKᵦ = 14 (at 25°C)

This relationship shows that the stronger the acid, the weaker its conjugate base and vice versa-a vital insight for predicting reaction tendencies.

Di- and Polybasic Acids and Polyacidic Bases

Certain acids, like sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) and phosphoric acid (H₃PO₄), can release more than one proton per molecule. These are polyprotic acids, and their ionization occurs in stages:

H₂A ⇌ H⁺ + HA⁻ (Kₐ₁)

HA⁻ ⇌ H⁺ + A²⁻ (Kₐ₂)

Each successive dissociation becomes less favorable, hence Kₐ₁ > Kₐ₂. Similarly, polyacidic bases like Ba(OH)₂ and Al(OH)₃ donate multiple OH⁻ ions per molecule, showing stepwise ionization.

Factors Affecting Acid Strength

The strength of an acid depends on several factors:

- Bond Strength: Weaker H–A bonds ionize more easily.

- Polarity: Highly polar bonds favor dissociation.

- Electronegativity: Greater electronegativity stabilizes the conjugate base.

- Atomic Size: Larger atoms hold hydrogen less tightly, increasing acidity.

Across a period, acid strength increases with electronegativity, whereas down a group it increases as bond dissociation energy decreases. For example:

HF < HCl < HBr < HI (acid strength increases down the group).

Common Ion Effect in the Ionization of Acids and Bases

The common ion effect suppresses ionization when a common ion is introduced into the equilibrium. For instance:

CH₃COOH ⇌ H⁺ + CH₃COO⁻

Adding sodium acetate (CH₃COONa) increases CH₃COO⁻ concentration, reducing the ionization of acetic acid. This principle plays a major role in buffer formation and salt hydrolysis.

Hydrolysis of Salts and the pH of Their Solutions

When acids and bases react in definite proportions, they form salts, which undergo ionization in water. The resulting cations and anions may either remain hydrated or interact with water molecules, depending on their nature. This interaction between water and the ions of salts is known as hydrolysis.

The pH of the solution changes based on whether the salt originates from a strong or weak acid or base. Salts of strong acids and strong bases do not undergo hydrolysis and hence produce neutral solutions (pH = 7). However, salts involving weak acids or weak bases exhibit hydrolysis, affecting the pH.

The hydrolysis of salts can be classified into three types:

- Salts of weak acid and strong base – e.g., CH₃COONa

- Salts of strong acid and weak base – e.g., NH₄Cl

- Salts of weak acid and weak base – e.g., CH₃COONH₄

(i) Salts of Weak Acid and Strong Base

Example: Sodium acetate (CH₃COONa)

Sodium acetate, being a salt of weak acetic acid and strong NaOH, ionizes completely in water:

CH₃COONa(aq) → CH₃COO⁻(aq) + Na⁺(aq)

The acetate ion (CH₃COO⁻) undergoes hydrolysis as follows:

CH₃COO⁻ + H₂O ⇌ CH₃COOH + OH⁻

Since acetic acid (CH₃COOH) is weak, the reaction increases the concentration of OH⁻ ions, making the solution basic (pH > 7).

(ii) Salts of Strong Acid and Weak Base

Example: Ammonium chloride (NH₄Cl)

Ammonium chloride dissociates completely:

NH₄Cl(aq) → NH₄⁺(aq) + Cl⁻(aq)

The ammonium ion (NH₄⁺) undergoes hydrolysis:

NH₄⁺ + H₂O ⇌ NH₄OH + H⁺

Since H⁺ concentration increases, the solution becomes acidic (pH < 7).

(iii) Salts of Weak Acid and Weak Base

Example: Ammonium acetate (CH₃COONH₄)

In this case, both ions undergo hydrolysis:

CH₃COO⁻ + NH₄⁺ + H₂O ⇌ CH₃COOH + NH₄OH

The resulting solution’s pH depends on the relative strengths of the acid and base involved. The relationship is given by:

pH = 7 + ½(pKᵦ – pKₐ)

If pKᵦ > pKₐ, the solution is acidic (pH < 7); if pKᵦ < pKₐ, the solution is basic (pH > 7).

Example:

If pKₐ (acetic acid) = 4.76 and pKᵦ (ammonium hydroxide) = 4.75, then:

pH = 7 + ½(4.75 – 4.76) = 7.005

Hence, the solution is nearly neutral.

Importance of Salt Hydrolysis

- Helps predict whether a salt solution is acidic, basic, or neutral.

- Important in understanding buffer systems that resist pH change.

- Plays a role in biological systems where pH maintenance is critical.

- Crucial for industrial and analytical chemistry, such as titration analysis and water treatment.

Conclusion

The study of ionization and hydrolysis reveals how acids, bases, and salts interact in aqueous solutions. Through parameters like Kₐ, Kᵦ, K𝑤, and pH, chemists can quantify acidity and alkalinity and predict solution behavior. Understanding these equilibria is key for mastering acid-base chemistry, buffer systems, and ionic reactions-vital concepts for NEET and JEE aspirants.

Get Social