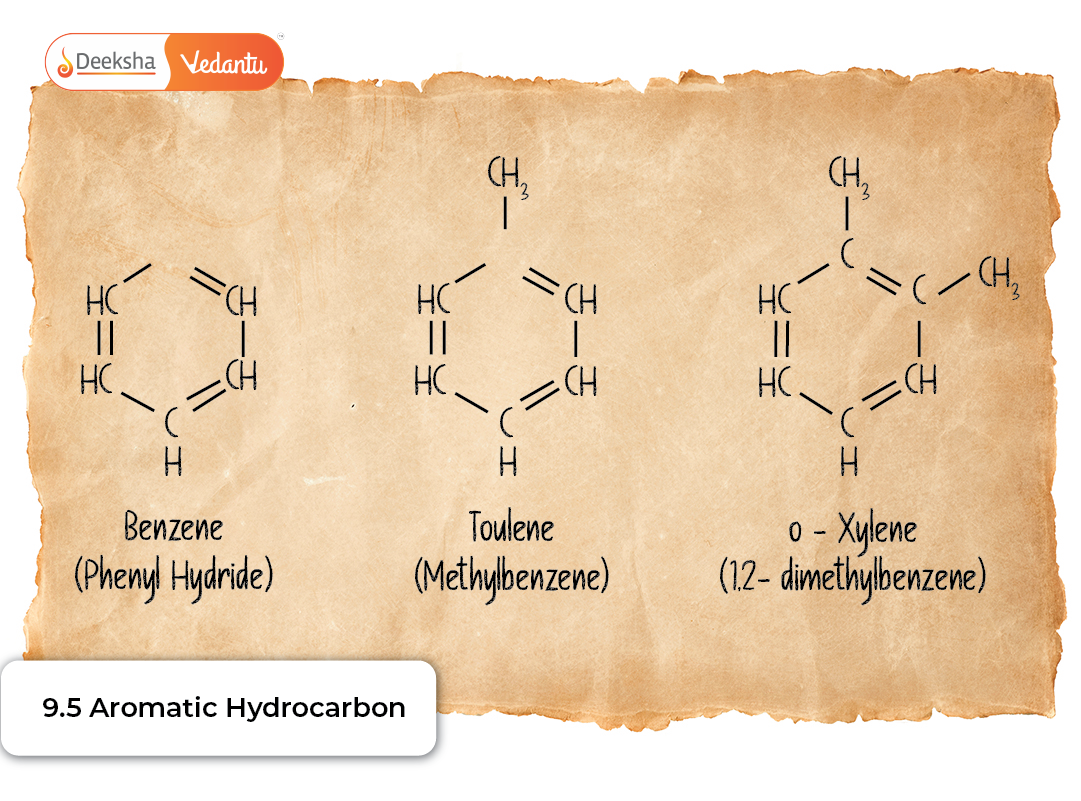

Aromatic hydrocarbons, also known as arenes, represent one of the most significant and widely studied families of organic compounds. Their name originates from their characteristic pleasant smell found in many natural aromatic compounds. Aromatic hydrocarbons contain one or more benzene rings, or similar cyclic, planar systems with fully delocalised π-electron clouds. This extended electron delocalisation imparts exceptional chemical stability, a phenomenon known as aromatic stabilization. Because of this unique stability, aromatic compounds behave very differently from ordinary alkanes, alkenes, and alkynes.

Despite being unsaturated, aromatic hydrocarbons do not readily undergo addition reactions because such reactions would disrupt the π-electron cloud and destroy aromaticity. Instead, they typically undergo electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions, allowing them to retain stability while undergoing chemical transformation. Aromatic hydrocarbons are essential in the chemical industry and biological systems, forming the basis of pharmaceuticals, polymers, dyes, agrochemicals, explosives, and numerous everyday materials.

Nomenclature and Isomerism

Naming aromatic hydrocarbons follows systematic IUPAC rules based on the structure of benzene. The presence and position of substituents influence the naming and classification of these compounds.

Basic Naming Rules

- The root name for all aromatic compounds containing a single ring is benzene.

- A substituent attached to the ring is simply prefixed to the name, e.g., chlorobenzene, nitrobenzene.

- When multiple substituents are present, their positions are indicated using numbering or prefixes.

- Substituents are numbered such that the lowest possible set of locants is achieved.

Ortho, Meta, and Para Notations

For disubstituted benzene derivatives, the relative positions of two substituents can be described using the traditional prefixes:

- Ortho (o-) → positions 1,2

- Meta (m-) → positions 1,3

- Para (p-) → positions 1,4

These designations are frequently used in older literature as well as modern industry and are particularly convenient for common molecules like o-xylene, m-dinitrobenzene, and p-chlorotoluene.

Examples

- Toluene (methylbenzene)

- Aniline (aminobenzene)

- o-Dichlorobenzene

- m-Nitrotoluene

- p-Ethylaniline

Types of Isomerism

Aromatic hydrocarbons show several forms of isomerism:

- Position isomerism: Substituents at different positions lead to distinct isomers.

- Chain isomerism: In alkylbenzenes, branching of side chains can lead to different structures.

- Functional group isomerism: In compounds with functional groups attached to benzene.

These isomeric variations influence both physical and chemical properties, making aromatic systems a rich area of study.

Structure of Benzene

Benzene is the simplest aromatic hydrocarbon, and understanding its structure is crucial for learning aromatic chemistry. Its molecular formula, C₆H₆, suggests a high degree of unsaturation. However, benzene does not behave like a typical unsaturated compound, which puzzled early chemists.

Key Features of Benzene Structure

- Benzene is a planar, hexagonal, cyclic molecule.

- Each carbon atom is sp² hybridised, forming three sigma bonds.

- The unhybridised p-orbitals on each carbon overlap sideways.

- This forms a continuous delocalised π-electron cloud above and below the ring.

- All carbon–carbon bonds in benzene have equal length (~1.39 Å), intermediate between single and double bonds.

Resonance in Benzene

Benzene is often represented by two Kekulé structures, which differ only in the positions of the double bonds. In reality, neither structure exists independently; instead, benzene is a resonance hybrid, with the π electrons fully delocalised across the ring.

This delocalisation:

- Increases stability

- Creates equal bond characteristics

- Reduces reactivity toward addition reactions

- Produces the unique aromatic character benzene is known for

The resonance energy of benzene reflects the extra stability gained due to delocalisation and is a key reason for benzene’s chemical behaviour.

Aromaticity (Hückel’s Rule)

Aromaticity is a unique type of stability exhibited by cyclic, planar, conjugated systems. It is governed by Hückel’s rule, which states that a molecule is aromatic if it contains:

- A cyclic structure

- A planar arrangement of atoms

- A fully conjugated π-electron system (i.e., continuous p-orbital overlap)

- (4n + 2) π electrons, where n = 0, 1, 2, 3…

Benzene possesses 6 π electrons, matching the (4n + 2) rule for n = 1, confirming its aromaticity.

Consequences of Aromaticity

- Extraordinary chemical stability

- Resistance to addition reactions

- Preference for electrophilic substitution

- Uniform bond lengths

- Lower heat of hydrogenation than expected for a typical triene

Aromaticity is a central concept in organic chemistry, frequently tested in competitive exams, making it essential for students to understand thoroughly.

Preparation of Benzene

Benzene can be synthesised through multiple classical organic reactions. Understanding these methods provides insight into synthetic routes and fundamental organic transformations.

1. Decarboxylation of Aromatic Acids

Heating sodium benzoate with soda lime produces benzene and sodium carbonate.

- C₆H₅COONa + NaOH → C₆H₆ + Na₂CO₃

This is a common laboratory preparation of benzene.

2. Reduction of Phenol

Phenol, when heated with zinc dust, reduces to benzene.

3. From Acetylene (Cyclotrimerisation)

Acetylene, under high temperature and pressure, undergoes trimerisation:

- 3 C₂H₂ → C₆H₆

This process demonstrates how simple alkynes can form aromatic rings.

4. From Diazonium Salts

Arenediazonium salts can be reduced to benzene using hypophosphorous acid.

5. Hydrodealkylation (Industrial Method)

Alkylbenzenes, especially toluene, can produce benzene through high‑temperature hydrodealkylation.

These methods highlight both lab-scale and industrial-scale routes to benzene.

Chemical Properties of Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Due to their stable aromatic ring, aromatic hydrocarbons primarily undergo electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS) reactions. These reactions preserve aromaticity while introducing new substituents.

1. Electrophilic Substitution Reactions

These reactions follow a consistent mechanism:

- Formation of a strong electrophile

- Electrophilic attack on the benzene ring forming a carbocation (sigma complex)

- Deprotonation to restore aromaticity

(a) Nitration

Reagents: Concentrated HNO₃ + H₂SO₄

- Benzene → Nitrobenzene

(b) Halogenation

Reagents: Br₂/FeBr₃ or Cl₂/FeCl₃

- Benzene → Bromobenzene/Chlorobenzene

(c) Sulphonation

Reagent: Fuming H₂SO₄

- Benzene → Benzene sulphonic acid

(d) Friedel–Crafts Alkylation

Reagents: Alkyl chloride + AlCl₃

- Benzene → Alkylbenzene

(e) Friedel–Crafts Acylation

Reagents: Acyl chloride + AlCl₃

- Benzene → Acylbenzene

2. Side‑Chain Oxidation

The side chains of alkylbenzenes can be oxidised fully to benzoic acid under strong oxidising conditions.

- Toluene + KMnO₄ → Benzoic acid

3. Addition Reactions (Under Drastic Conditions)

Although rare, benzene may undergo addition reactions such as hydrogenation at elevated temperatures and pressures, but this destroys aromaticity.

4. Combustion

Aromatic hydrocarbons burn with a sooty flame due to their high carbon content.

Physical Properties of Aromatic Hydrocarbons

- Most arenes are liquids or low‑melting solids at room temperature.

- insoluble in water but readily dissolve in organic solvents.

- They possess characteristic sweet or pungent odours.

- Their melting and boiling points are higher than analogous aliphatic compounds due to effective π–π stacking.

- Aromatic rings contribute to dense electron clouds, influencing polarity and intermolecular forces.

JEE/NEET Practice Questions

Q1. (NEET Level) Which of the following compounds is aromatic according to Hückel’s rule?

(a) Cyclobutadiene

(b) Cyclooctatetraene

(c) Benzene

(d) Cyclohexene

Answer: (c) Benzene

Q2. (JEE Level) In nitration of benzene, the role of concentrated H₂SO₄ is to:

(a) produce NO₂⁺ electrophile

(b) act as a dehydrating agent only

(c) neutralise HNO₃

(d) oxidise benzene

Answer: (a) produce NO₂⁺ electrophile

Q3. (NEET Level) Which reagent is used in the Friedel–Crafts alkylation of benzene?

(a) KOH

(b) AlCl₃

(c) NaNH₂

(d) ZnCl₂

Answer: (b) AlCl₃

Q4. (JEE Level) The number of electrophilic substitution products possible for monochlorination of toluene is:

(a) 1

(b) 2

(c) 3

(d) 4

Answer: (c) 3 (o-, m-, p-chlorotoluene)

Q5. (NEET Level) When toluene is oxidised with KMnO₄, the major product is:

(a) Benzaldehyde

(b) Benzoic acid

(c) Benzyl alcohol

(d) Benzene

Answer: (b) Benzoic acid

Q6. (JEE Level) Which of the following statements is NOT true about benzene?

(a) All C–C bonds are equal in length

(b) It follows Hückel’s rule

(c) It readily undergoes addition reactions

(d) It is stabilised by resonance

Answer: (c) It readily undergoes addition reactions

Q7. (NEET Level) What is the hybridisation of carbon atoms in benzene?

(a) sp

(b) sp²

(c) sp³

(d) dsp²

Answer: (b) sp²

Q8. (JEE Level) The electrophile generated during sulphonation of benzene is:

(a) SO₃

(b) H₂SO₄⁺

(c) SO₃H⁺

(d) HSO₄⁻

Answer: (c) SO₃H⁺

Q9. (NEET Level) Which one of the following burns with the most sooty flame?

(a) Cyclohexane

(b) Hexane

(c) Benzene

(d) Propane

Answer: (c) Benzene

Q10. (JEE Level) Identify the product of Friedel–Crafts acylation of benzene using CH₃COCl/AlCl₃.

(a) Toluene

(b) Acetophenone

(c) Benzaldehyde

(d) Benzyl chloride

Answer: (b) Acetophenone

FAQs

Q1. Why does benzene prefer substitution reactions over addition reactions?

Benzene possesses a stable conjugated π-electron cloud. An addition reaction would break aromaticity by disrupting this electron delocalisation. Substitution reactions allow the ring to preserve aromatic stability.

Q2. What is Hückel’s rule and why is it important?

Hückel’s rule states that a molecule is aromatic if it has (4n + 2) π electrons in a cyclic, planar, conjugated system. It helps determine whether a cyclic compound will exhibit aromatic stability.

Q3. Why are all C–C bond lengths in benzene identical?

Because benzene is a resonance hybrid with delocalised electrons, the distinction between single and double bonds disappears, resulting in equal C–C bond lengths.

Q4. How do o-, m-, and p‑isomers differ?

They differ in the relative positions of substituents on the benzene ring. This affects boiling points, melting points, polarity, and chemical behaviour.

Q5. What type of flame do aromatic hydrocarbons burn with?

Arenes burn with a sooty flame because of their high carbon percentage and incomplete combustion.

Conclusion

Aromatic hydrocarbons form one of the most important families of organic compounds due to their exceptional stability and reactivity patterns. Their resonance‑stabilised structures make them essential in industrial chemistry, pharmaceuticals, dyes, polymers, and numerous modern materials. Understanding their nomenclature, structure, aromaticity, and reaction mechanisms is vital for mastering organic chemistry and excelling in competitive exams.

At Deeksha Vedantu, students are guided to understand aromatic hydrocarbons conceptually and apply these concepts effectively during board exams and competitive examinations.

Get Social