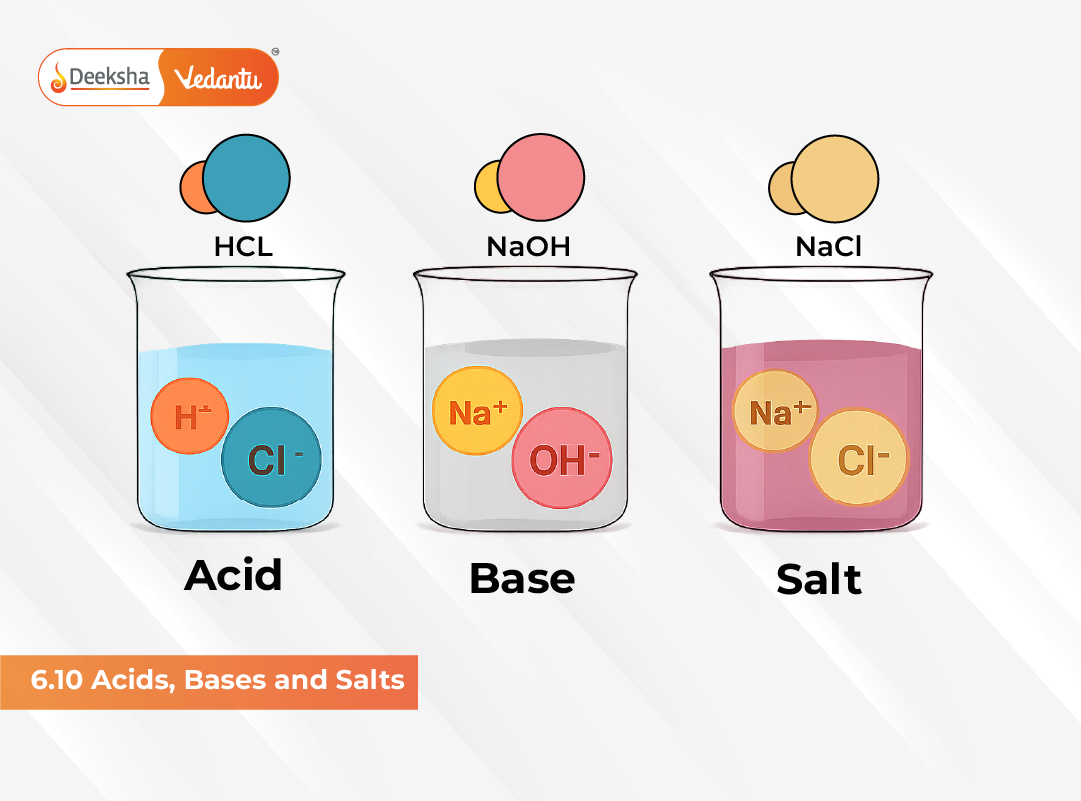

Acids, bases, and salts form the foundation of numerous chemical reactions and are central to understanding the behavior of substances in various environments – from biological systems to industrial processes. These substances are omnipresent in nature and daily life. Acids are found in fruits, digestive juices, and even rainfall, while bases are present in soaps, detergents, and household cleaning products. Salts constitute essential dietary minerals and industrial chemicals.

For instance, hydrochloric acid (HCl) secreted in the human stomach plays a vital role in digestion by maintaining a pH around 1.5. Acetic acid, the main component of vinegar, contributes to its tangy flavor. Citrus fruits like lemons and oranges contain citric acid and ascorbic acid (vitamin C), while tartaric acid occurs naturally in tamarind and grapes. On the other hand, bases such as sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and ammonium hydroxide (NH₄OH) are common in industrial cleaning and laboratory applications. When acids and bases combine in appropriate proportions, they neutralize each other to form salts and water.

The term acid originates from the Latin word acidus, meaning “sour.” Acids typically have a sour taste, turn blue litmus paper red, and react with active metals to release hydrogen gas. Bases taste bitter, feel slippery or soapy, and turn red litmus paper blue. These observable properties make it easy to distinguish between acids and bases in simple laboratory tests.

Common examples of salts include sodium chloride (NaCl) – a key dietary component, barium sulfate (BaSO₄) used in radiography, and sodium nitrate (NaNO₃) used in fertilizers. Salts are products of neutralization reactions and are essential in both industrial chemistry and biological systems.

Dissolution and Ionic Nature of Salts

In their solid state, salts like NaCl consist of positively charged cations (Na⁺) and negatively charged anions (Cl⁻) arranged in a highly ordered crystalline lattice held together by electrostatic forces. These forces are governed by Coulomb’s Law, which states that the force between two charges is inversely proportional to the dielectric constant of the medium.

Water, with a dielectric constant of about 80, is an exceptional solvent for ionic compounds. When NaCl is added to water, the high dielectric constant significantly weakens the attraction between Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions, allowing them to separate. Each ion becomes surrounded by water molecules – a process known as hydration. The partially negative oxygen atoms of water molecules surround Na⁺ ions, while the hydrogen atoms surround Cl⁻ ions. This stabilizes the ions, allowing them to move freely and conduct electricity.

The dissolution of ionic compounds thus converts them into electrolytes, explaining why saline solutions conduct electricity while pure water does not.

Comparison of Acid Ionization Strengths

Acids vary widely in their ability to ionize in water. For example, both hydrochloric acid (HCl) and acetic acid (CH₃COOH) are polar covalent compounds, yet HCl dissociates completely, while acetic acid ionizes only partially (about 5%). This difference arises from variations in bond strength, polarity, and the solvation energy released during ionization.

Strong acids like HCl and HNO₃ produce nearly 100% hydrogen ions (H⁺) in aqueous solution, whereas weak acids like acetic acid reach a state of equilibrium between the ionized and unionized forms:

CH₃COOH ⇌ CH₃COO⁻ + H⁺

The position of equilibrium and the extent of ionization depend on the acid’s dissociation constant (Ka). A high Ka value indicates strong ionization, while a low Ka value denotes a weak acid.

Arrhenius Concept of Acids and Bases

Proposed by Svante Arrhenius in 1884, this theory provides the earliest and simplest explanation of acid-base behavior in aqueous solutions:

- Acids are substances that release hydrogen ions (H⁺) or hydronium ions (H₃O⁺) when dissolved in water.

Example: HCl → H⁺ + Cl⁻ or HCl + H₂O → H₃O⁺ + Cl⁻ - Bases are substances that release hydroxide ions (OH⁻) when dissolved in water.

Example: NaOH → Na⁺ + OH⁻

Although limited to aqueous media, this model introduced the idea of ionization as the key mechanism for acid-base behavior.

Hydronium Ion Formation

Since free hydrogen ions cannot exist independently in solution, they attach to water molecules to form hydronium ions (H₃O⁺):

H⁺ + H₂O → H₃O⁺

Hydronium ions are responsible for the acidity of aqueous solutions and act as proton carriers in most acid-base reactions.

However, the Arrhenius model cannot explain acid-base reactions that occur without water or those that do not involve hydroxide ions, such as the neutralization of ammonia (NH₃) by hydrogen chloride (HCl) gas.

The Brønsted-Lowry Concept of Acids and Bases

In 1923, Johannes Brønsted and Thomas Lowry expanded the acid-base concept to include proton transfer reactions occurring in any solvent system. They defined:

- Acid: A proton (H⁺) donor.

- Base: A proton acceptor.

This theory emphasizes the transfer of protons rather than the formation of ions in water, making it more versatile.

Example: Ammonia and Water

NH₃(aq) + H₂O(l) ⇌ NH₄⁺(aq) + OH⁻(aq)

Here, NH₃ acts as a base (accepts a proton from water), while H₂O acts as an acid (donates a proton). The products – NH₄⁺ and OH⁻ – form a conjugate acid-base pair.

This system also demonstrates the reversibility of acid-base interactions, as the conjugate acid (NH₄⁺) and conjugate base (OH⁻) can react to reform NH₃ and H₂O.

Conjugate Acid-Base Pairs

Each acid-base pair differs by one proton. For example:

HCl + H₂O ⇌ H₃O⁺ + Cl⁻

In this reaction:

- HCl is the acid, and Cl⁻ is its conjugate base.

- H₂O is the base, and H₃O⁺ is its conjugate acid.

The stronger the acid, the weaker its conjugate base, and vice versa.

Example Problem

Identify conjugate acid-base pairs in the reaction:

HCO₃⁻ + H₂O ⇌ H₂CO₃ + OH⁻

- HCO₃⁻ acts as a base (accepts a proton).

- H₂CO₃ is the conjugate acid.

- H₂O acts as an acid (donates a proton).

- OH⁻ is the conjugate base.

This example illustrates the dynamic equilibrium in aqueous systems, where acids and bases continuously interchange protons.

Lewis Acids and Bases

The Lewis theory proposed by G.N. Lewis in 1923 provides an even broader perspective by focusing on electron transfer instead of proton movement. According to this concept:

- A Lewis Acid is an electron pair acceptor.

- A Lewis Base is an electron pair donor.

This framework encompasses many reactions that the Brønsted-Lowry theory cannot explain, including complex formation and coordination reactions.

Example: Formation of a Coordinate Bond

BF₃ + NH₃ → BF₃·NH₃

- BF₃ acts as a Lewis acid because the boron atom has an empty orbital capable of accepting a lone pair.

- NH₃ acts as a Lewis base as it donates a lone pair from its nitrogen atom.

Other examples include AlCl₃, Fe³⁺, and Zn²⁺, which serve as Lewis acids, and molecules like H₂O, NH₃, and OH⁻, which act as Lewis bases.

Comparative Overview of Acid-Base Theories

| Theory | Key Concept | Acid Definition | Base Definition | Typical Example |

| Arrhenius | Ionization in water | Produces H⁺ or H₃O⁺ in water | Produces OH⁻ in water | HCl, NaOH |

| Brønsted-Lowry | Proton transfer | Donates H⁺ | Accepts H⁺ | NH₃ + H₂O ⇌ NH₄⁺ + OH⁻ |

| Lewis | Electron pair exchange | Accepts electron pair | Donates electron pair | BF₃ + NH₃ → BF₃·NH₃ |

Applications and Real-World Importance

The understanding of acid-base chemistry has vast applications across multiple fields:

- Industrial Chemistry: Production of fertilizers, soaps, dyes, and explosives relies on acid-base reactions.

- Environmental Science: Acid rain formation and ocean acidification depend on equilibrium between atmospheric gases and water.

- Medicine: The concept of pH is critical in drug formulation and physiological pH balance.

- Analytical Chemistry: Acid-base titrations help determine the concentration of unknown solutions.

- Everyday Life: Baking soda, antacids, and cleaning agents work through controlled acid-base reactions.

Conclusion

The theories proposed by Arrhenius, Brønsted-Lowry, and Lewis collectively explain the diverse nature of acids, bases, and salts across aqueous and non-aqueous systems. These models help predict reaction mechanisms, equilibrium positions, and ionic behavior under varying conditions. A solid grasp of these principles equips NEET and JEE students to tackle conceptual and numerical questions related to titrations, pH, conjugate systems, and buffer solutions – building the bridge between theoretical chemistry and real-world applications.

Get Social