When a chemical reaction reaches a state in which the concentrations of reactants and products remain constant over time, the mixture is said to be in a state of chemical equilibrium. This section focuses on the quantitative relationship between these concentrations — how they relate and how we can predict equilibrium compositions under different conditions.

The composition of an equilibrium mixture depends on temperature, pressure, and concentration. Understanding this relationship helps chemists design industrial processes such as the manufacture of NH₃, H₂, and CaO, where optimizing yield is crucial.

Deriving the Law of Chemical Equilibrium

Consider a general reversible reaction:

A + B ⇌ C + D

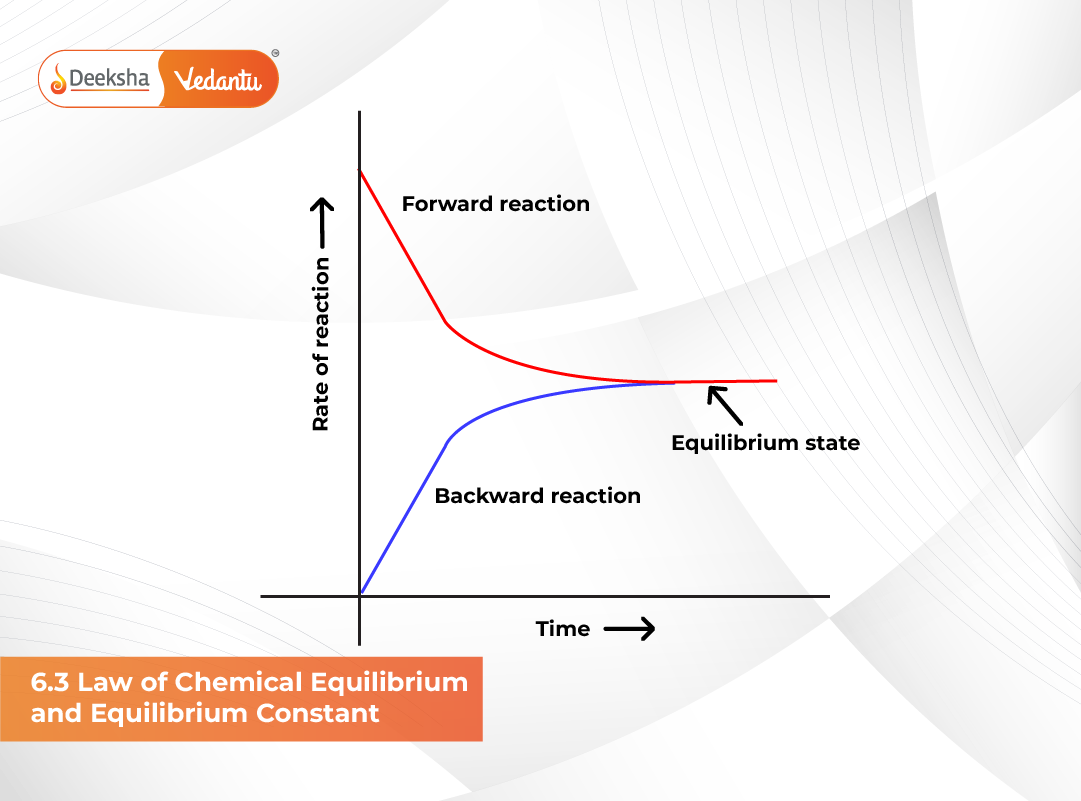

At equilibrium, the rate of the forward reaction (formation of C and D) equals the rate of the reverse reaction (regeneration of A and B). Based on experimental studies, Cato Maximilian Guldberg and Peter Waage (1864) proposed the Law of Mass Action, which states:

At a given temperature, the rate of a chemical reaction is directly proportional to the product of the active masses (concentrations) of the reactants, each raised to the power equal to its stoichiometric coefficient.

For the reaction above, the equilibrium condition can be written as:

Kc = [C][D] / [A][B]

Here, Kc is called the equilibrium constant for the reaction at a given temperature. This constant value depends only on temperature and not on the initial concentrations of the reactants or products.

Experimental Verification – The Reaction of Hydrogen and Iodine

To verify the law of chemical equilibrium, consider the reversible reaction:

H₂(g) + I₂(g) ⇌ 2HI(g)

Experiments were conducted by taking different initial amounts of hydrogen and iodine under constant temperature (731 K). The equilibrium concentrations of H₂, I₂, and HI were measured for several trials. It was found that even when the starting amounts were different, the ratio:

[HI]² / [H₂][I₂]

remained constant at equilibrium.

This confirmed that the expression involving the equilibrium concentrations of products and reactants yields a constant value at a fixed temperature — the equilibrium constant.

| Experiment No. | Initial Concentration (mol L⁻¹) | Equilibrium Concentration (mol L⁻¹) |

| 1 | H₂ = 1.0, I₂ = 1.0 | HI = 1.14 × 10⁻² |

| 2 | H₂ = 2.0, I₂ = 1.0 | HI = 1.14 × 10⁻² |

| 3 | H₂ = 3.0, I₂ = 2.0 | HI = 1.14 × 10⁻² |

The constancy of Kc across experiments proves that equilibrium is governed by the Law of Chemical Equilibrium.

Expression for the Equilibrium Constant (Kc)

For a general reaction:

aA + bB ⇌ cC + dD

the equilibrium constant expression is written as:

Kc = [C]ᶜ[D]ᵈ / [A]ᵃ[B]ᵇ

Here, the terms within brackets represent the molar concentrations of each species at equilibrium, and the exponents correspond to their stoichiometric coefficients.

Example: For the reaction:

4NH₃(g) + 5O₂(g) ⇌ 4NO(g) + 6H₂O(g)

The equilibrium constant is expressed as:

Kc = [NO]⁴[H₂O]⁶ / [NH₃]⁴[O₂]⁵

This relationship shows that equilibrium constants can vary greatly depending on reaction conditions and molecular species involved.

Characteristics of the Equilibrium Constant (Kc)

- Dependence on Temperature: Kc changes with temperature; increasing temperature may shift equilibrium position, altering its value.

- Independence from Initial Concentrations: Kc remains constant for a specific reaction at a given temperature regardless of how much reactant or product is initially present.

- Dimensionless Form: In many cases, equilibrium constants are written in dimensionless form by dividing by a standard concentration (1 mol L⁻¹).

- Indication of Reaction Extent: A large Kc (>10³) indicates product dominance, while a small Kc (<10⁻³) indicates reactant dominance.

Relationship Between Forward and Reverse Equilibrium Constants

For a reversible reaction:

A + B ⇌ C + D

Let the equilibrium constant for the forward reaction be Kf and for the reverse reaction be Kr.

Kc (forward) = [C][D] / [A][B]

Kc (reverse) = [A][B] / [C][D]

Thus,

Kc (reverse) = 1 / Kc (forward)

This means that when a reaction is written in the reverse direction, the equilibrium constant is the reciprocal of the forward one.

Multiple Reactions and Equilibrium Constants

If a chemical equation is multiplied by a factor n, the equilibrium constant becomes Kcⁿ. For example:

nH₂(g) + nI₂(g) ⇌ 2nHI(g)

Here, Kc‘ = (Kc)ⁿ

Similarly, if a reaction is divided by a number, the equilibrium constant becomes the root of the original constant.

Relation Between Equilibrium Constants for a General Reaction and Its Multiples

| Chemical Equation | Relation Between Equilibrium Constants |

| aA + bB ⇌ cC + dD | Kc |

| cC + dD ⇌ aA + bB | 1/Kc |

| naA + nbB ⇌ ncC + ndD | (Kc)ⁿ |

Sample Calculations

Problem 1:

Calculate Kc for the formation of NH₃ from N₂ and H₂ at 500 K.

Given: [NH₃] = 1.5 × 10⁻² M, [H₂] = 3.0 × 10⁻³ M, [N₂] = 1.2 × 10⁻³ M.

Solution:

N₂(g) + 3H₂(g) ⇌ 2NH₃(g)

Kc = [NH₃]² / [N₂][H₂]³

Kc = (1.5 × 10⁻²)² / (1.2 × 10⁻³ × (3.0 × 10⁻³)³)

Kc = 0.355 × 10³ = 3.55 × 10²

Problem 2:

For the reaction N₂(g) + O₂(g) ⇌ 2NO(g),

if [N₂] = 3.0 × 10⁻³ M, [O₂] = 4.2 × 10⁻³ M, and [NO] = 2.8 × 10⁻³ M, find Kc.

Solution:

Kc = [NO]² / [N₂][O₂]

Kc = (2.8 × 10⁻³)² / (3.0 × 10⁻³ × 4.2 × 10⁻³)

Kc = 0.622

Key Points for NEET & JEE

- Understanding equilibrium constants helps predict the extent of reactions under given conditions.

- Graph-based and numerical problems often involve calculating Kc and interpreting its physical significance.

- The Law of Chemical Equilibrium is a core foundation for later topics such as Le Chatelier’s Principle and Ionic Equilibria.

- Kc values are temperature-dependent; expect questions comparing equilibria at different temperatures.

FAQs

Q1. What is the Law of Chemical Equilibrium?

It states that for a reversible reaction at constant temperature, the ratio of the product of the equilibrium concentrations of products to that of reactants, each raised to their respective stoichiometric coefficients, is constant.

Q2. What does the value of Kc signify?

A high Kc (>10³) indicates product dominance, while a low Kc (<10⁻³) signifies reactant dominance.

Q3. How is the equilibrium constant for the reverse reaction related to the forward reaction?

K(reverse) = 1 / K(forward).

Q4. Does Kc depend on pressure or concentration?

No, Kc depends only on temperature for a given reaction.

Q5. What are the units of Kc?

The units depend on the overall change in moles (Δn) of gaseous species; for example, molⁿ L⁻ⁿ where n = (moles of products – moles of reactants).

Conclusion

The Law of Chemical Equilibrium provides a quantitative foundation for understanding how reactions achieve balance between reactants and products. The equilibrium constant Kc serves as a key parameter in predicting reaction behavior, evaluating yields, and analyzing chemical systems under varying conditions. Mastery of these concepts is essential for solving equilibrium-based questions in NEET, JEE, and other advanced chemistry exams.

Get Social