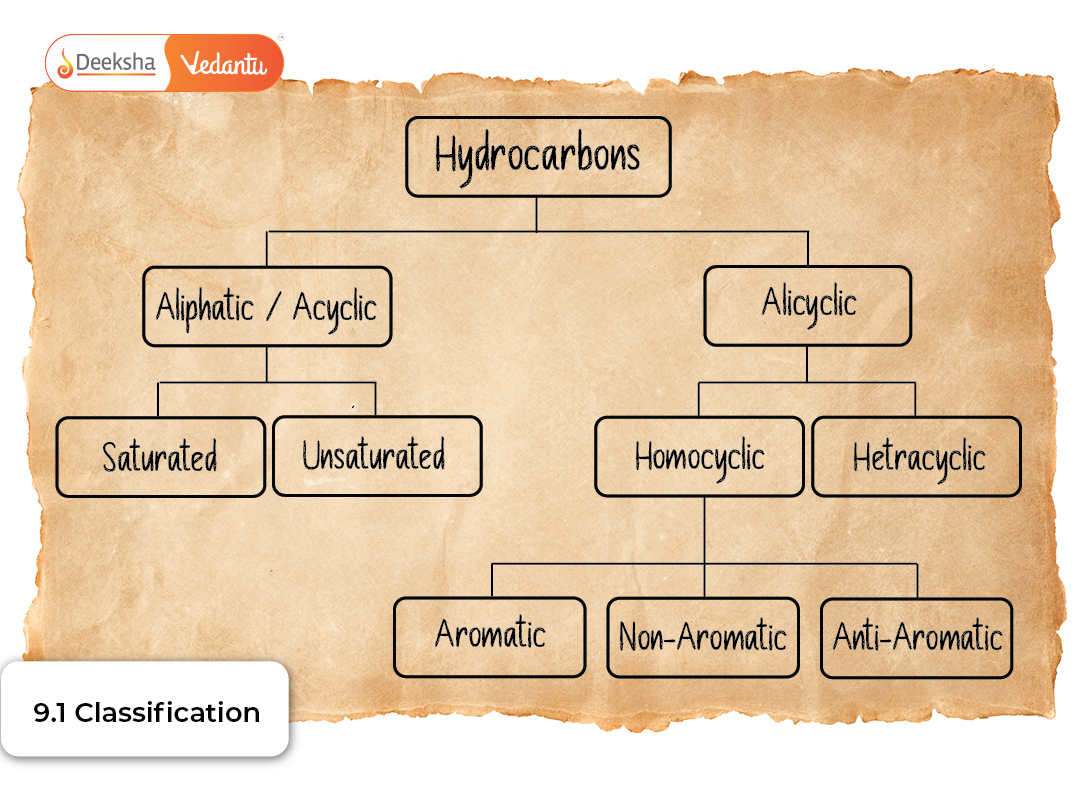

Hydrocarbons are organic compounds composed exclusively of carbon and hydrogen atoms, and their classification is the gateway to mastering organic chemistry. This classification is not only a theoretical framework but also a practical tool that helps students predict reaction mechanisms, stability, and the behaviour of organic compounds in different chemical environments. The entire field of organic chemistry builds upon a deep understanding of how hydrocarbons are grouped, how they differ structurally, and how these differences influence their reactivity.

This expanded explanation dives deeper into each classification type, elaborating on properties, structural variations, industrial relevance, and conceptual importance for both board exams and competitive exams such as JEE and NEET.

Meaning of Hydrocarbons

Hydrocarbons contain only carbon and hydrogen atoms, yet they display immense structural diversity. They originate from natural sources such as petroleum, coal, and natural gas, and form the backbone for all complex organic molecules encountered in biological systems, fuels, polymers, pharmaceuticals, and industrial chemicals.

Hydrocarbons can be classified in two complementary ways:

- Based on saturation, where we focus on the nature of carbon–carbon bonds.

- Based on structure, where we observe how carbon atoms are arranged within the molecule.

Both methods are essential because a molecule’s bonding (single, double, triple bonds) influences its reactivity, whereas its structure (open-chain or cyclic) affects its stability, strain, isomerism, and aromatic character.

Classification Based on Saturation

This approach looks at the type of bonds connecting carbon atoms and how these bonds influence the molecule’s reactivity.

1. Saturated Hydrocarbons (Alkanes)

Saturated hydrocarbons contain only single covalent bonds (σ bonds) between carbon atoms. These σ bonds are strong, stable, and difficult to break, resulting in low chemical reactivity.

Detailed characteristics:

- General formula: CₙH₂ₙ₊₂ (for open-chain alkanes)

- All carbon atoms are sp³ hybridised, giving tetrahedral geometry

- Bond angles of approximately 109.5° minimise repulsion

- Show conformational isomerism (e.g., staggered and eclipsed forms in ethane)

- Chemically inert under normal conditions

Alkanes undergo reactions only under specific conditions:

- Combustion: Produces CO₂, H₂O, and heat, making alkanes widely used as fuels.

- Substitution reactions: Typically free-radical halogenation.

- Oxidation: Harsh oxidising conditions required.

Examples include:

- Methane (CH₄): Fuel and chemical feedstock

- Ethane (C₂H₆): LPG component

- Propane (C₃H₈): Domestic and industrial fuel

2. Unsaturated Hydrocarbons

Unsaturated hydrocarbons contain one or more multiple bonds (C=C or C≡C). These π bonds are weaker and more exposed, making the molecules more reactive than alkanes.

a. Alkenes (C=C)

Alkenes contain at least one carbon–carbon double bond and are central to many addition reactions.

Key properties:

- General formula: CₙH₂ₙ

- Carbon atoms are sp² hybridised, forming a trigonal planar geometry

- Presence of a π bond leads to restricted rotation, giving rise to cis–trans isomerism

- React readily with electrophiles due to the electron-rich π bond

Common examples:

- Ethene (C₂H₄): Industrially vital for producing polymers like polyethylene

- Propene (C₃H₆): Used in polypropylene production

b. Alkynes (C≡C)

Alkynes contain at least one carbon–carbon triple bond, consisting of one σ bond and two π bonds.

Key points:

- General formula: CₙH₂ₙ₋₂

- Carbon atoms are sp hybridised, creating a linear structure

- High s-character leads to stronger C–H bonds, making terminal alkynes weakly acidic

- Undergo electrophilic addition, oxidation, and polymer-forming reactions

Examples:

- Ethyne (C₂H₂): Used in oxy-acetylene welding

- Propyne (C₃H₄): A building block in organic synthesis

Thus, unsaturated hydrocarbons are far more reactive due to accessible π electrons, making them central to industrial organic transformations.

Classification Based on Structure

This method focuses on how carbon atoms are connected within the molecule.

1. Acyclic (Open-Chain) Hydrocarbons

Acyclic hydrocarbons contain carbon atoms arranged in straight or branched chains without forming rings.

They include:

- Saturated acyclic hydrocarbons (alkanes)

- Unsaturated acyclic hydrocarbons (alkenes and alkynes)

Examples:

- n-Butane: A straight-chain alkane

- 2-Methylpropene: A branched alkene

Open-chain structures are the simplest and form the basis for naming conventions and understanding isomerism.

2. Cyclic Hydrocarbons

These hydrocarbons contain one or more rings of carbon atoms.

They are of two major types:

a. Alicyclic Hydrocarbons

Alicyclic hydrocarbons resemble aliphatic compounds but have ring structures.

Important features:

- May contain single or multiple bonds

- Can show ring strain (especially in small rings like cyclopropane)

- Exhibit substitution and addition reactions depending on saturation

Examples:

- Cyclohexane (C₆H₁₂): Exists in stable chair and boat conformations

- Cyclopentene (C₅H₈): Contains a double bond within the ring

b. Aromatic Hydrocarbons

Aromatic hydrocarbons (arenes) contain a delocalised π-electron cloud across a cyclic framework.

Defining features:

- Obey Hückel’s rule: (4n + 2) π electrons

- Highly stable due to resonance

- Undergo electrophilic substitution reactions instead of addition

Examples:

- Benzene (C₆H₆): The simplest aromatic compound

- Toluene (C₇H₈): Methyl-substituted benzene

Aromatic hydrocarbons are essential in pharmaceuticals, dyes, polymers, and fuels.

Summary Table of Classification

| Basis | Type | Key Features | Examples |

| Saturation | Saturated | Only C–C single bonds | CH₄, C₂H₆ |

| Unsaturated (double) | Contains C=C | C₂H₄ | |

| Unsaturated (triple) | Contains C≡C | C₂H₂ | |

| Structure | Acyclic | Straight/branched chains | Butane |

| Alicyclic | Non-aromatic rings | Cyclohexane | |

| Aromatic | Delocalised π electrons | Benzene |

FAQs

Q1. What is the simplest hydrocarbon?

Methane (CH₄) is the simplest and the first member of the alkane series.

Q2. Why are alkenes more reactive than alkanes?

Because the π bond in alkenes is weaker and more exposed, making it easier for electrophiles to attack.

Q3. How do you identify if a compound is aromatic?

Check if it is cyclic, planar, conjugated, and follows Hückel’s rule (4n + 2 π electrons).

Q4. What is the difference between alicyclic and aromatic hydrocarbons?

Alicyclic compounds are non-aromatic rings, while aromatic compounds contain delocalised π-electron clouds.

Q5. Why are terminal alkynes acidic?

Terminal alkynes have an sp‑hybridised carbon which holds electrons closer to the nucleus, increasing acidity.

Conclusion

The classification of hydrocarbons is essential for understanding their structure, bonding, and reactions. It forms the basis for studying advanced organic concepts like mechanisms, isomerism, and aromatic chemistry. At Deeksha Vedantu, students learn these concepts with clarity and real‑world application, ensuring strong fundamentals for board and competitive exams.

Get Social