The concept of oxidation number offers a systematic way to explain redox reactions, especially in compounds where electron transfer is not direct or obvious. It helps chemists keep track of electron shifts and determine which elements are oxidized or reduced in a reaction.

Introduction to Oxidation Number

Consider the reaction:

2H₂(g) + O₂(g) → 2H₂O(l)

In this reaction, hydrogen is oxidized while oxygen is reduced. Although the actual electron transfer is not complete, we can visualize hydrogen atoms going from a neutral (0) state to a +1 state in water, while oxygen moves from 0 in O₂ to -2 in H₂O. This apparent electron shift illustrates oxidation and reduction using oxidation numbers.

In essence, the oxidation number represents the hypothetical charge that an atom would have if all its bonds were purely ionic. It helps us assign oxidation states even in covalent compounds.

Concept and Significance

In reactions such as:

H₂S(g) + Cl₂(g) → 2HCl(g) + S(s)

CH₄(g) + 4Cl₂(g) → CCl₄(l) + 4HCl(g)

The electron transfer between hydrogen, chlorine, and sulfur is not complete. Instead of tracking individual electrons, chemists use oxidation numbers to determine the direction of electron shifts. This simplifies the classification of redox reactions.

Rules for Assigning Oxidation Numbers

A systematic set of rules helps assign oxidation numbers to atoms in molecules or ions:

- Elements in Free State: The oxidation number of an element in its uncombined state is always zero.

Example: H₂, O₂, Cl₂, Na, P₄ → oxidation number = 0 - Monatomic Ions: The oxidation number equals the ion’s charge.

Example: Na⁺ = +1, Mg²⁺ = +2, Cl⁻ = -1 - Oxygen: Usually has an oxidation number of -2, except in peroxides (-1) and compounds with fluorine (+2).

Example: H₂O (-2), H₂O₂ (-1), OF₂ (+2) - Hydrogen: Usually +1, except in metal hydrides where it is -1.

Example: H₂O (+1), NaH (-1) - Halogens: Fluorine always has -1. Other halogens (Cl, Br, I) are -1 unless bonded with oxygen or fluorine.

Example: HCl (-1), ClO₂ (+4) - Neutral Compounds: The sum of oxidation numbers equals zero.

Example: H₂O → 2(+1) + (-2) = 0 - Polyatomic Ions: The sum of oxidation numbers equals the ionic charge.

Example: SO₄²⁻ → S + 4(-2) = -2 → S = +6

Examples of Oxidation Numbers

| Group | 1 | 2 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| Example | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl |

| Highest Oxidation State | +1 | +2 | +3 | +4 | +5 | +6 | +7 |

This table indicates how elements from different groups exhibit varying oxidation states, helping predict redox behavior.

Stock Notation System

German chemist Alfred Stock introduced the Stock notation, where oxidation numbers are represented using Roman numerals in parentheses.

Examples:

- FeCl₂ → Iron(II) chloride

- FeCl₃ → Iron(III) chloride

- SnCl₂ → Tin(II) chloride

- SnCl₄ → Tin(IV) chloride

This notation clarifies the oxidation state of the metal involved in a compound.

Oxidation and Reduction in Terms of Oxidation Number

- Oxidation: Increase in oxidation number of an element.

- Reduction: Decrease in oxidation number of an element.

- Oxidizing Agent: Species that causes oxidation (itself reduced).

- Reducing Agent: Species that causes reduction (itself oxidized).

Example Problem:

Cu₂O(s) + CuS(s) → Cu(s) + SO₂(g)

Solution:

Assign oxidation numbers:

Cu in Cu₂O → +1

Cu in CuS → +2

S in CuS → -2 → S becomes +4 in SO₂

Hence, both Cu₂O and CuS are involved in redox changes — confirming this as a redox reaction.

Types of Redox Reactions

- Combination Reactions:

A + B → C

Example: C(s) + O₂(g) → CO₂(g) - Decomposition Reactions:

AB → A + B

Example: 2NaH → 2Na + H₂ - Displacement Reactions:

A + BC → AC + B

These include:- Metal Displacement: Zn + CuSO₄ → ZnSO₄ + Cu

- Non-Metal Displacement: Cl₂ + 2KI → 2KCl + I₂

- Disproportionation Reactions:

The same element undergoes oxidation and reduction simultaneously.

Example: 2H₂O₂ → 2H₂O + O₂

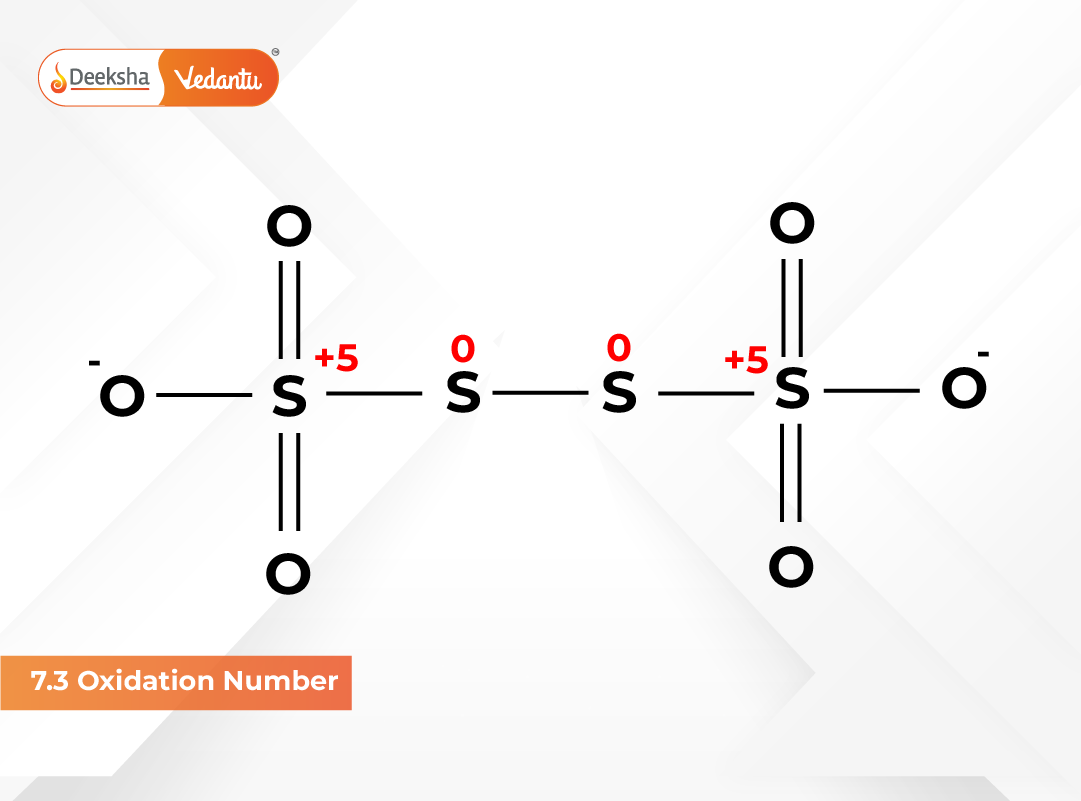

Paradox of Fractional Oxidation Numbers

Certain compounds have fractional oxidation numbers because of resonance or delocalized bonding. Examples include:

- C₃O₂ (carbon = +4/3)

- Br₃O₈ (bromine = +16/3)

- Na₂S₄O₆ (sulfur = +2.5)

Fractional values arise when equivalent atoms share different oxidation states within the same molecule.

Methods for Balancing Redox Reactions

Two main methods exist for balancing redox equations:

(a) Oxidation Number Method

- Write correct formulas for reactants and products.

- Assign oxidation numbers to all atoms.

- Calculate the increase/decrease in oxidation number.

- Equalize the total electrons gained and lost.

- Balance remaining atoms (H, O, etc.) accordingly.

(b) Half-Reaction Method

- Divide the reaction into oxidation and reduction halves.

- Balance atoms other than O and H.

- Balance O by adding H₂O; balance H by adding H⁺.

- Add e⁻ to balance charge.

- For basic solutions, replace H⁺ with H₂O and OH⁻.

- Combine the half-reactions ensuring electron count equality.

- Confirm mass and charge balance.

Example – Acidic Medium:

Fe²⁺ + Cr₂O₇²⁻ + H⁺ → Fe³⁺ + Cr³⁺ + H₂O

Balanced form:

6Fe²⁺ + Cr₂O₇²⁻ + 14H⁺ → 6Fe³⁺ + 2Cr³⁺ + 7H₂O

Example – Basic Medium:

MnO₄⁻ + I⁻ → MnO₂ + IO₃⁻

Balanced form:

6I⁻ + 2MnO₄⁻ + 4H₂O → 3I₂ + 2MnO₂ + 8OH⁻

Redox Reactions as the Basis for Titrations

Redox titrations use oxidation-reduction reactions to determine the concentration of an oxidizing or reducing agent. They rely on color change to indicate endpoints.

(i) Self-Indicator Method

Some reagents act as their own indicators. Example: KMnO₄ (permanganate) turns from colorless to pink as it oxidizes substances.

(ii) External Indicator Method

When no color change occurs, an external indicator such as diphenylamine is used. Example: K₂Cr₂O₇ oxidizes diphenylamine, turning blue at the endpoint.

(iii) Iodometric Method

This involves oxidation of iodide ions to iodine, which reacts with starch to form a blue color.

Example: Cu²⁺ + 4I⁻ → 2CuI + I₂

I₂ + 2S₂O₃²⁻ → 2I⁻ + S₄O₆²⁻

The color disappears when all iodine is consumed, marking the endpoint.

Limitations of Oxidation Number Concept

While oxidation numbers are useful, they simplify the actual electron distribution and are sometimes unable to accurately represent covalent bonding or delocalized electrons. Modern definitions of oxidation and reduction emphasize electron density shifts rather than full transfers.

FAQs

Q1. What is an oxidation number?

It is a numerical value assigned to an atom that represents its degree of oxidation or reduction in a compound.

Q2. Why do we use oxidation numbers?

They help identify which elements are oxidized or reduced and make balancing redox equations easier.

Q3. What are the exceptions to oxidation numbers of oxygen and hydrogen?

Oxygen has -1 in peroxides and +2 in compounds with fluorine. Hydrogen has -1 in metal hydrides.

Q4. What is disproportionation?

It is a reaction in which the same element is both oxidized and reduced.

Q5. What is the Stock notation?

It uses Roman numerals to represent the oxidation state of metals in compounds (e.g., FeCl₃ → Iron(III) chloride).

Q6. What are the two main methods to balance redox reactions?

The oxidation number method and the half-reaction method.

Conclusion

The oxidation number approach provides a logical framework to understand redox reactions. It helps identify oxidation and reduction even in covalent compounds, predict reaction feasibility, and balance complex redox equations. This concept bridges classical and modern views of redox chemistry, offering clarity and precision in chemical analysis.

Get Social