The concept of equilibrium lies at the heart of chemistry and helps explain how and why reactions occur. Most reactions do not go to completion; instead, they reach a state where the forward and reverse reactions occur at equal rates. This state is known as chemical equilibrium.

This unit explores two main types of equilibrium:

- Physical Equilibrium – related to physical processes such as phase changes.

- Chemical Equilibrium – related to reversible chemical reactions.

Understanding equilibrium helps students explain reaction direction, predict the extent of reactions, and solve problems related to Le Chatelier’s principle, equilibrium constant, and ionic equilibrium—key concepts tested in NEET and JEE exams.

Equilibrium in Physical Processes

Many physical processes are reversible and reach equilibrium when opposing changes occur at equal rates.

Example 1: Evaporation and Condensation

In a closed container, water evaporates and condenses simultaneously. At equilibrium, the rate of evaporation equals the rate of condensation, and vapor pressure remains constant.

H₂O(l) ⇌ H₂O(g)

Example 2: Dissolution of Solids in Liquids

At equilibrium:

NaCl(s) ⇌ Na⁺(aq) + Cl⁻(aq)

The rate of dissolution equals the rate of crystallization. The concentration of solute remains constant in the solution.

Example 3: Dissolution of Gases in Liquids

When a gas dissolves in a liquid, equilibrium is established between dissolved and undissolved gas molecules.

Henry’s Law relates pressure and solubility:

p = kₕx

where:

- p = partial pressure of gas,

- x = mole fraction of gas in liquid,

- kₕ = Henry’s constant.

Higher pressure or lower temperature increases gas solubility.

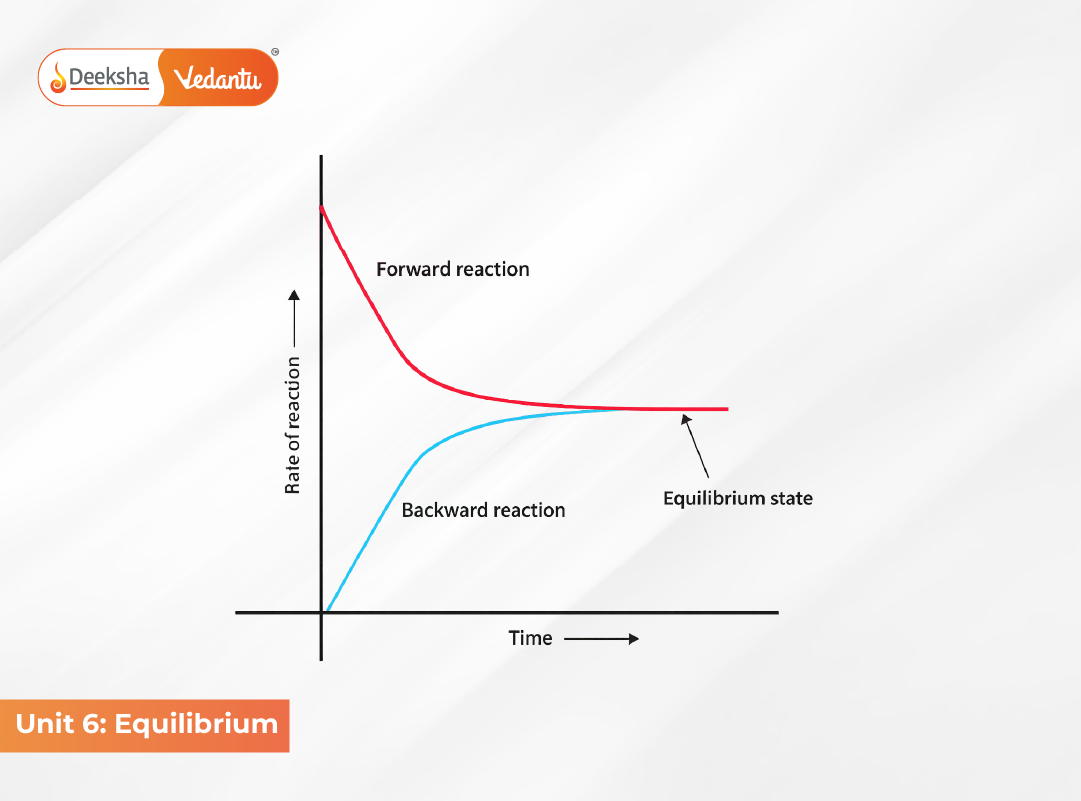

Equilibrium in Chemical Processes – Dynamic Nature

Chemical equilibrium is dynamic—both forward and backward reactions continue, but their rates become equal. Concentrations of reactants and products remain constant.

Example:

N₂O₄(g) ⇌ 2NO₂(g)

At equilibrium, the rate of dissociation of N₂O₄ equals the rate of formation of N₂O₄ from NO₂.

Law of Chemical Equilibrium

For a general reversible reaction:

aA + bB ⇌ cC + dD

At equilibrium:

Rate of forward reaction = Rate of backward reaction

k₁[A]ᵃ[B]ᵇ = k₂[C]ᶜ[D]ᵈ

Dividing both sides,

([C]c [D]d)/([A]a [B]b) = k1/k2 = Kc

Here, Kc is the equilibrium constant in terms of concentration.

For gases, we can also define:

Kp = Kc(RT)(Δn)

where Δn = (moles of gaseous products – moles of gaseous reactants)

Characteristics of Equilibrium Constant

- It has a fixed value at a given temperature.

- It indicates the extent of a reaction.

- It is independent of the initial concentrations.

- It changes with temperature but not with catalysts.

A high Kc (> 10³) means the reaction favors products; a low Kc (< 10⁻³) favors reactants.

Applications of Equilibrium Constant

- Predicting the direction of reactions using the reaction quotient (Qc):

- If Qc < Kc → Reaction moves forward.

- If Qc > Kc → Reaction moves backward.

- If Qc = Kc → System at equilibrium.

- Calculating equilibrium concentrations using Kc expressions.

- Predicting the extent of reaction (high Kc → nearly complete reaction).

Factors Affecting Equilibrium – Le Chatelier’s Principle

Le Chatelier’s Principle states that if an external change is applied to a system at equilibrium, the system shifts to counteract the change.

(a) Effect of Concentration

Increasing reactant concentration shifts equilibrium toward products.

Example:

N₂(g) + 3H₂(g) ⇌ 2NH₃(g)

Adding N₂ or H₂ drives equilibrium rightward (toward NH₃).

(b) Effect of Pressure

For gaseous reactions:

- Increasing pressure favors fewer moles of gas.

- Decreasing pressure favors more moles of gas.

(c) Effect of Temperature

- Exothermic reactions (ΔH < 0): Higher temperature shifts equilibrium backward.

- Endothermic reactions (ΔH > 0): Higher temperature shifts equilibrium forward.

(d) Effect of Catalyst

A catalyst speeds up both forward and backward reactions equally, helping equilibrium reach faster but not altering its position.

Ionic Equilibrium in Solutions

This section deals with equilibrium in ionic compounds that dissolve in water to produce ions.

(a) Electrolytes

- Strong electrolytes completely ionize (e.g., HCl, NaOH).

- Weak electrolytes partially ionize (e.g., CH₃COOH, NH₄OH).

(b) Ionization of Weak Electrolytes

HA ⇌ H⁺ + A⁻

Ionization constant:

Kₐ = [H⁺][A⁻] / [HA]

(c) Relationship Between Ka and Kb

For a conjugate acid-base pair:

Kₐ × Kᵦ = Kᵥ

At 25°C, Kᵥ = 1 × 10⁻¹⁴

(d) pH and pOH

pH = –log [H⁺]

pOH = –log [OH⁻]

pH + pOH = 14 (at 298 K)

(e) Ionic Product of Water

H₂O(l) ⇌ H⁺(aq) + OH⁻(aq)

Kᵥ = [H⁺][OH⁻] = 1 × 10⁻¹⁴ (at 25°C)

Common Ion Effect

The suppression of ionization of a weak electrolyte by the presence of a strong electrolyte having a common ion.

Example:

Addition of NaCl to HCl solution suppresses ionization of HCl due to the common ion Cl⁻.

Buffer Solutions

A buffer solution resists change in pH upon addition of small amounts of acid or base.

Types:

- Acidic buffer (CH₃COOH + CH₃COONa)

- Basic buffer (NH₄OH + NH₄Cl)

Henderson–Hasselbalch Equation:

pH = pKa + log ([salt]/[acid])

Solubility Product (Ksp)

When a sparingly soluble salt dissolves in water:

AB ⇌ A⁺ + B⁻

Ksp = [A⁺][B⁻]

It helps predict precipitation or solubility under different ionic conditions.

If ionic product (Qsp) > Ksp, precipitation occurs.

If Qsp < Ksp, more salt dissolves.

Hydrolysis of Salts

Hydrolysis occurs when salt ions react with water to produce acidic or basic solutions.

Example:

CH₃COONa + H₂O ⇌ CH₃COOH + NaOH

Degree of hydrolysis (h):

h = √(Kw / Ka × C)

pH of hydrolyzed solution depends on Ka and Kb of ions involved.

Applications of Equilibrium in Daily Life

- Industrial synthesis (Haber’s process, Contact process).

- Buffer control in biological systems.

- Understanding acid rain, corrosion, and water treatment.

FAQs

Q1. What is chemical equilibrium?

It is the state where forward and reverse reactions occur at equal rates and concentrations of reactants and products remain constant.

Q2. Why is equilibrium dynamic in nature?

Because the reactions continue to occur in both directions at equal rates.

Q3. How does temperature affect equilibrium constant?

Equilibrium constant changes with temperature — increases for endothermic and decreases for exothermic reactions.

Q4. What is the difference between Kc and Kp?

Kc is based on molar concentrations, while Kp is based on partial pressures.

Q5. What is a buffer solution?

A solution that maintains its pH upon addition of small amounts of acid or base.

Conclusion

Equilibrium is a cornerstone concept in chemistry that connects thermodynamics and kinetics. Understanding equilibrium constants, ionic equilibria, and Le Chatelier’s principle enables chemists to predict and control reaction behavior. Mastery of these topics provides a strong foundation for solving advanced problems in NEET and JEE Chemistry.

Get Social